|

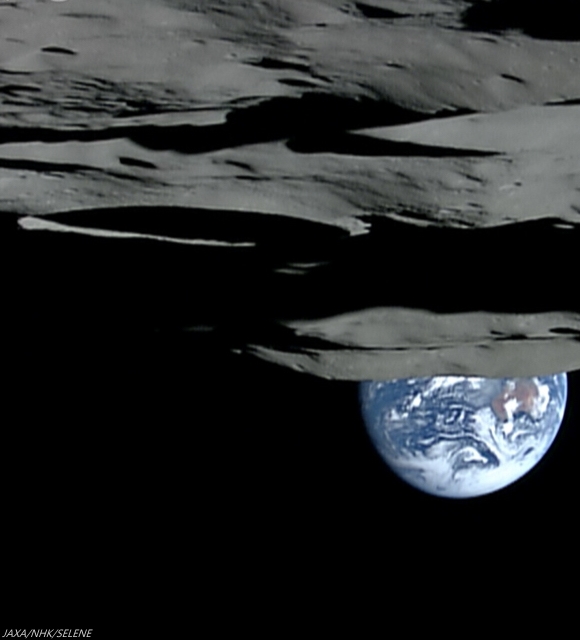

| The vastness of space, and the inviting terra firma of Earth and Moon. LROC Featured Image, May 7, 2014. LROC WAC M1145896768C, LRO orbit 20898, February 1, 2014 [NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University]. |

The Once and Future Moon

Smithsonian Air & Space

The LRO Camera Team recently released a newly obtained, beautiful image of the Earth above the north pole of the Moon. In the history of lunar exploration, Earthrise photos have always been widely displayed and admired. Capturing the iconic image of a magnificent blue and white Earth hanging over the barren, gray surface of the Moon is one of the most memorable moments of man’s first flight to the Moon by Apollo 8 in December 1968.

This picture graced the covers of newspapers and magazines everywhere; it inspired a million words of prose and created the modern environmental movement as we know it. Few single images have had such pervasive and lasting power.

This picture graced the covers of newspapers and magazines everywhere; it inspired a million words of prose and created the modern environmental movement as we know it. Few single images have had such pervasive and lasting power.

|

| Apollo 8's overview effect: Iconic Earthrise image, AS08-14-2383, Bill Anders' serendipitous photograph of Earth as the first manned flight to the Moon swung around from the farside, December 24, 1968 [NASA/JSC]. |

The Apollo 11 crew landed on the lunar surface a few months after that Earthrise photo was circulated. During this and subsequent missions (all on the central near side of the Moon), it was reported by the media that Earth always appears stationary in the same part of the sky as seen from the Moon’s surface.

In November 1969, the Apollo 12 crew put up a large inverted umbrella antenna to improve communication data rates from the lunar surface; it had to be set-up and aligned, but once pointed at Earth, it remained pointed at it forever.

In November 1969, the Apollo 12 crew put up a large inverted umbrella antenna to improve communication data rates from the lunar surface; it had to be set-up and aligned, but once pointed at Earth, it remained pointed at it forever.

Because the Moon orbits the Earth and is in synchronous rotation with its orbital period, we always see the same side. Hence, there is a near side (the hemisphere we see from Earth) and a far side (the side we cannot see from Earth; it is often mistakenly called the “dark side”).

A consequence of this synchronous rotation is that from the Moon, the Earth appears stationary in the sky, just as the hub of a bicycle wheel remains stationary from the viewpoint of one of its spokes. Thus, while the Sun rises and sets according to the slow rotation rate of the Moon (one complete rotation every 708 hours, half day and half night), the Earth is always in the same spot in the sky. Of course, because it is illuminated by the Sun, it changes its phase on the same timescale as does the Moon as seen from Earth, although reversed (a full Moon on Earth is a new Earth from the Moon and vice versa.) From the far side of the Moon, one does not see the Earth at all.

Are spectacular views of Earthrise only visible from spacecraft in orbit about the Moon? Not quite.

Two points about the Moon’s orbit make the story a bit more complicated. First, the Moon’s orbit around the Earth is not circular but elliptical, its distance ranging from 363,000 km up to 405,000 km from the Earth. Second, the plane of the Moon’s orbit is inclined about 5 degrees to the ecliptic (the plane of the Earth-Moon system’s orbit around the Sun). These two facts mean that the Moon librates, or “wobbles” both left and right (an effect of its elliptical orbit) and up and down (an effect of the inclination of its orbital plane). These librations are not overwhelmingly significant, but result in some interesting effects around the limb of the Moon – the great circle made up by the 90 degrees east and west longitude lines, including both poles.

Two points about the Moon’s orbit make the story a bit more complicated. First, the Moon’s orbit around the Earth is not circular but elliptical, its distance ranging from 363,000 km up to 405,000 km from the Earth. Second, the plane of the Moon’s orbit is inclined about 5 degrees to the ecliptic (the plane of the Earth-Moon system’s orbit around the Sun). These two facts mean that the Moon librates, or “wobbles” both left and right (an effect of its elliptical orbit) and up and down (an effect of the inclination of its orbital plane). These librations are not overwhelmingly significant, but result in some interesting effects around the limb of the Moon – the great circle made up by the 90 degrees east and west longitude lines, including both poles.

|

| Earthset, from 1080p video captured from Japan's lunar orbiter SELENE-1 (Kaguya) October 31, 2007, as spacecraft and camera, in polar orbit, began its track north from the south pole (on the rim of Shackleton crater, center left) over the Moon's farside, leaving Earth to set behind Malapert massif, a nearside fragment of the rim of immense South Pole-Aitken impact basin [JAXA/NHK/SELENE]. |

The longitudinal libration is about 8 degrees, so the observer on the lunar limb would see the Earth slowly rise above the horizon and clear it by its apparent diameter, then slowly sink below the horizon by the same amount. That Earthrise will be slow indeed – it will take a couple of days for the full disk of the Earth to rise above the horizon. This cycle would repeat on a monthly timescale, as the Moon completes one revolution around the Earth.

Similarly, one would also see the Earth rise and set at the poles of the Moon, although to a different magnitude. The polar view is almost completely dominated by the latitudinal libration, caused by the inclination of the Moon’s orbital plane. This variation is about 6.5 degrees (it includes the Moon’s spin axis obliquity of 1.5 degrees) and would vary on a similar monthly timescale. These variations will become important if future lunar inhabitants live at the poles, as I think likely. As the Earth will sometimes be out of direct view, it is likely that we will depend on relay satellites for continuous communication. Polar inhabitants will also see a “different” Sun from what they’re accustomed to on Earth – at the lunar poles, the sun rotates around the horizon, rather than rising and setting.

|

| Cernan and Earth. At Taurus Littrow, Earth maintains its position. Ground controllers did occasionally admonished Apollo 17 Cmdr. Gene Cernan's partner Jack Schmidt for lifting his solar visor to get a better look at a rock, from time to time, during the last walks on the Moon. But at this point, however, as he traded poses with Schmidt using Earth as a backdrop, Cernan did briefly lift his visor halfway, allowing posterity an atypical view of an actual human face on the Moon in December 1972 (AS17-134-20471) [NASA/JSC]. |

Dr. Paul D. Spudis is a senior staff scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston. This column was originally published by Smithsonian Air & Space online, and his website can be found at www.spudislunarresources.com. The opinions he expressed here are his own, but these are better informed than most.

No comments:

Post a Comment