|

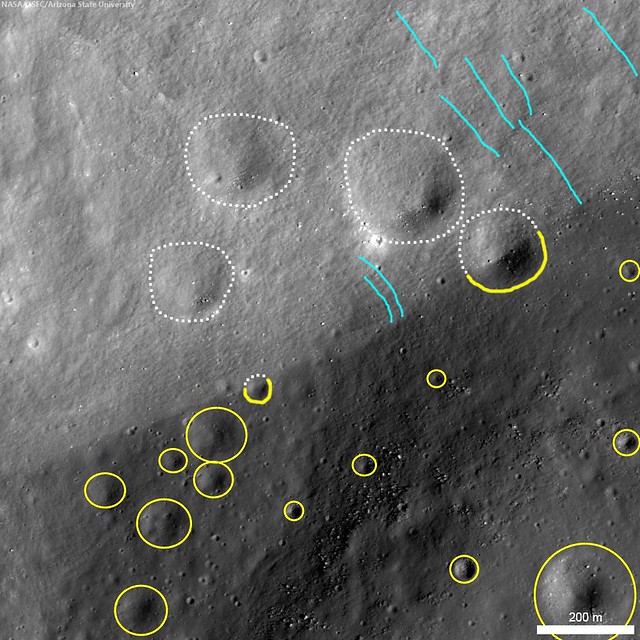

| Portion of the northwest wall of Steno Q intersects with a slump block terrace. The steep wall (upper left) appears smooth but lineated (some of this linear pattern is traced in cyan). The relatively flat-lying terrace (bottom right) preserves more craters (outlined in yellow). Dotted lines indicate craters partially destroyed by the gradual creep of materials downslope. Image field of view is 1.5 km. LROC Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) observation M191931820, LRO orbit 13319, May 17, 2012; 63° incidence, resolution 1.54 meters, from 156 km over 29.09°N, 157.3°E [NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University]. |

J. Stopar

LROC News System

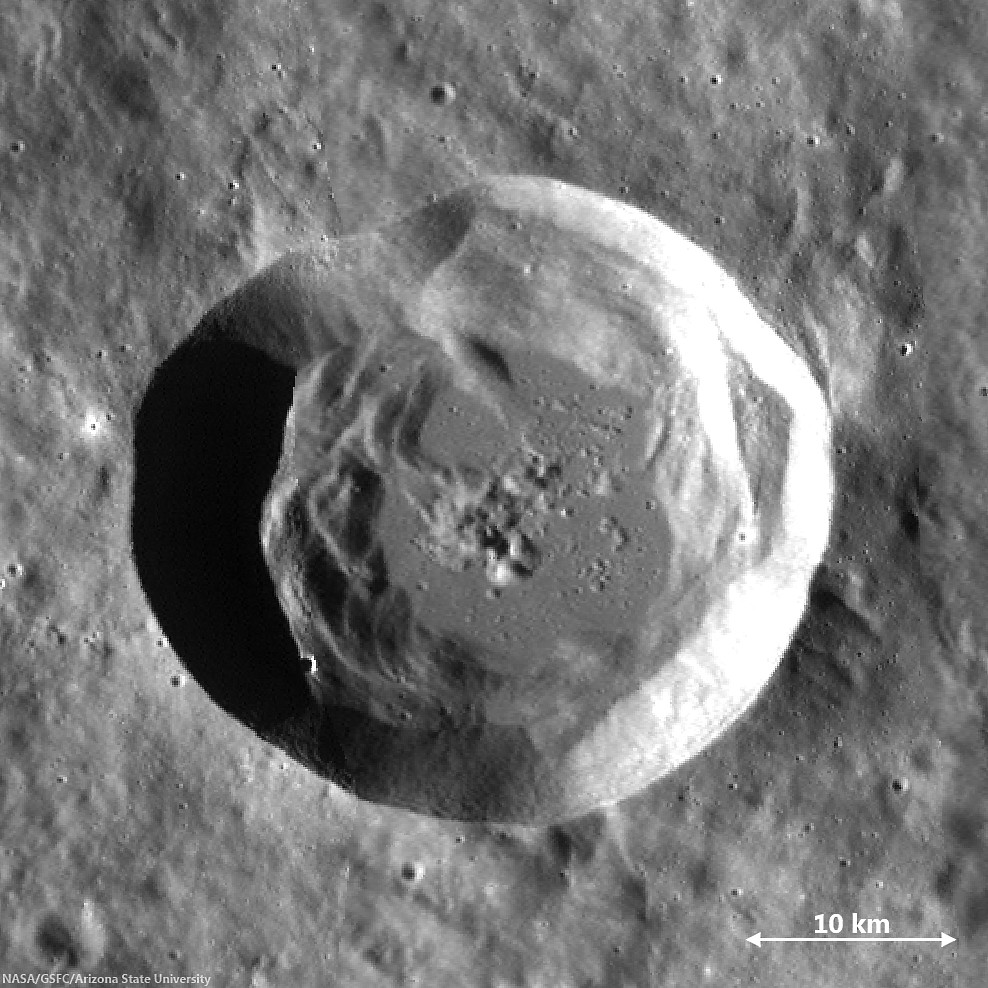

Looking at many of the LROC featured images, you might wonder why the floors and terraces of large craters often seem to have more superposed craters than the walls. The image of Steno Q, a complex 32-km diameter crater located east of Mare Moscoviense, at 29.064°N, 157.746°E, is shown below, is an example. The number of superposed craters of a given size per unit area is related to the age of the surface. Generally, older surfaces have more craters. Because the number of superposed craters (crater size frequency distribution) is related to the age of the surface, you might surmise that the walls of Steno Q are younger than the flat-lying portions of the floor and terraces. Over time, resurfacing events, such as gradual in-filling of the crater (like at Jansen U crater) or floods of mare lava (like at Flamsteed P), can change the observed density of superposed craters. Why then do the flat-lying portions of the floor and terraces of many craters like Steno Q seem to be older than the walls?

Large portions of the walls of Steno Q are steep, with slopes of 15° to more than 30°, while the floor and terraces are relatively flat. Areas with higher crater density such as the impact melt pond on the crater floor and the terrace shown in the opening image, correlate with the flatter areas. The opening image shows a part of the wall of Steno Q where it intersects a portion of a flat-lying terrace. Here, material covers parts of several small craters near the base of the wall. This portion of the crater wall exhibits slopes greater than 30° from horizontal, making it one of the steeper parts of the crater and enhancing the downward movement of material. The wall material creeping downslope, possibly driven by seismic events or shaking caused by other nearby impacts, has few visible blocks or fractures, and thus probably consists of unconsolidated fine-grained fragments and grains. The downward creep of the unconsolidated materials gradually buries craters near the base of the wall.

The creep process also distorts and destroys craters superposed on the walls (see opening image above). Thus, sloping surfaces of unconsolidated materials do not preserve craters as well as flat and more coherent surfaces. Therefore, when interpreting crater densities, scientists consider both topography of the surface and its consolidation. Surfaces experiencing creep are often characterized by a linear or hatched pattern, as is the wall of Steno Q. This pattern is sometimes referred to as elephant skin texture.

Even though the walls and floor were formed at the same time, the walls now have a lower superposed crater density caused by creep and resurfacing. Eventually, perhaps in billions of years, Steno Q will be worn down to a shallow depression and disappear altogether.

Using the full-resolution NAC mosaic, HERE, you can compare the crater populations found in Steno Q for yourself!

Related LROC Featured Images:

Near the Summit of Malapert Mountain

Post impact modification of Klute W

Downhill creep or flow

Slumping rim of Darwin C

Melt Boundary

Pile Up

LROC News System

Looking at many of the LROC featured images, you might wonder why the floors and terraces of large craters often seem to have more superposed craters than the walls. The image of Steno Q, a complex 32-km diameter crater located east of Mare Moscoviense, at 29.064°N, 157.746°E, is shown below, is an example. The number of superposed craters of a given size per unit area is related to the age of the surface. Generally, older surfaces have more craters. Because the number of superposed craters (crater size frequency distribution) is related to the age of the surface, you might surmise that the walls of Steno Q are younger than the flat-lying portions of the floor and terraces. Over time, resurfacing events, such as gradual in-filling of the crater (like at Jansen U crater) or floods of mare lava (like at Flamsteed P), can change the observed density of superposed craters. Why then do the flat-lying portions of the floor and terraces of many craters like Steno Q seem to be older than the walls?

|

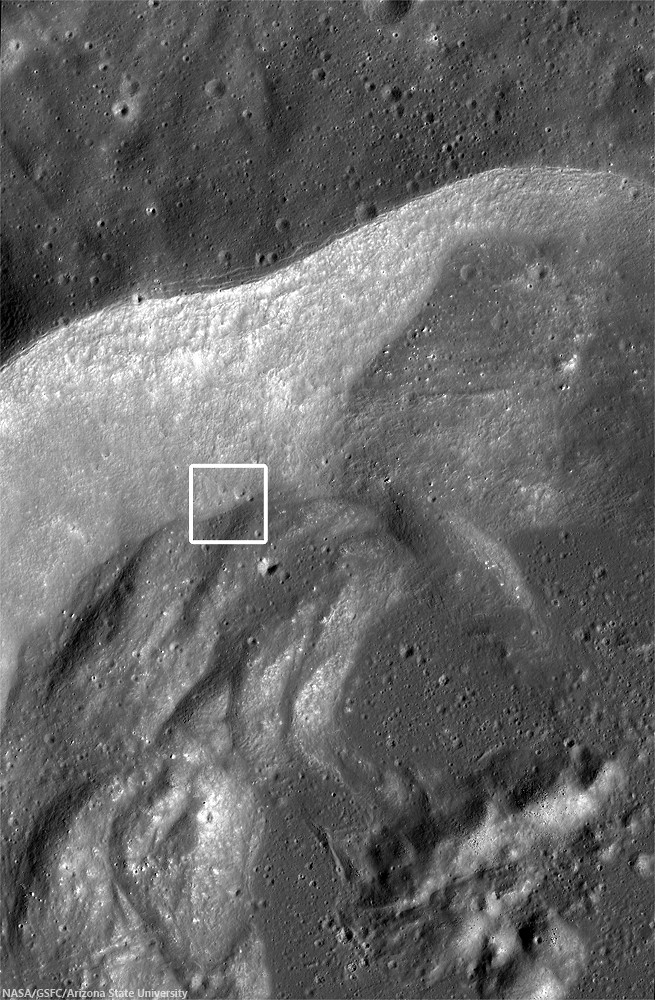

| Northwest portion of Steno Q crater. While box is 1.5 km field of view shown at high-resolution in the LROC Featured Image released December 9, 2013 [NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University]. |

|

| Steno Q crater, east of Mare Moscoviense, in the farside highland terrain [NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University]. |

Even though the walls and floor were formed at the same time, the walls now have a lower superposed crater density caused by creep and resurfacing. Eventually, perhaps in billions of years, Steno Q will be worn down to a shallow depression and disappear altogether.

Using the full-resolution NAC mosaic, HERE, you can compare the crater populations found in Steno Q for yourself!

Related LROC Featured Images:

Near the Summit of Malapert Mountain

Post impact modification of Klute W

Downhill creep or flow

Slumping rim of Darwin C

Melt Boundary

Pile Up

No comments:

Post a Comment